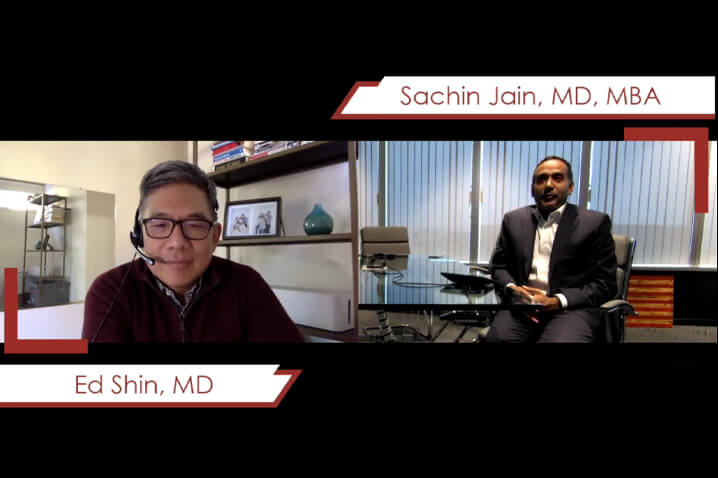

Sachin Jain on the Importance of Social Determinants of Health

Sachin Jain, MD, CEO of SCAN Health, has spent much of his career studying social determinants of health (SDoH) like poverty, racism, and pollution. These often lead to major healthcare disparities due to factors like vitamin deficiencies, exposure to mold, and unclean drinking water. Dr. Jain discussed these issues — along with health equity and public health interventions — in a recent webinar.

Read on below for highlights from his conversation with Edward Shin, MD, CEO of Quality Reviews.

Lots of “Self-Celebration” for Little Impact

In Dr. Jain’s experience, many healthcare organizations claim to center social determinants of health. In reality, however, this provide a “false sense of security and accomplishment.” He expresses that the issues run deeper in society, often relating to poverty and racism.

While working for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dr. Jain discovered that very few public health interventions actually made a difference when looking at large groups of individuals.

“We make ourselves feel better. We think, ‘We’re introducing medical rides program for poor people, and therefore, we’ve solved their healthcare access problems,'” Dr. Jain said.

Unfortunately, programs like these aren’t enough to solve long-standing issues.

Another example he cited was post-discharge meal programs. While they may help patients who have been immediately discharged from inpatient care, they don’t address long-term food insecurity and the healthcare disparities that occur as a result.

Fighting Healthcare Disparities at a Higher Level

Many healthcare providers believe they’ve finished their jobs once the patient leaves their offices. However, cultural organizations like African American medical groups and Korean American medical groups work around the clock to address the unique social determinants of health in their communities.

Hospital systems can work with these cultural groups to create positive change in the communities most impacted by social determinants of health. Dr. Jain encouraged healthcare workers to also work with professional societies and even the government to achieve health equity for vulnerable patients.

He also believes that healthcare organizations should be trying to training, hiring, and competitively compensating people who live within in the community.

“That’s a very different statement of our commitment, and it’s a different way of actually serving the community,” Dr. Jain said.

Overcoming Provider Burnout

Dr. Jain and Dr. Shin also discussed the increase in provider burnout, which has increased in recent years. During the pandemic, busy workloads and short staffing contributed to this significantly. Administrators, who tend to ask their staff to work harder and in less time, often exacerbate the problem.

“To be really blunt, if you’re not practicing, it’s very easy to tell people what to do,” Dr. Jain said.

And many efforts to help providers act as a bandaid, he believes.

“I think we’ve dealt with this issue by telling people to meditate and go to yoga retreats and give them access to the Headspace app,” Dr. Jain said. “Nothing against the app, but I think we’re treating the symptoms, not necessarily the cause.”

Taking on fewer patients, Dr. Jain believes, should be the goal. Managing a smaller caseload can decrease the risk of burnout — but with so many hospital systems overwhelmed, it is understandable that the medical community might encourage mental health care and meditation apps.

Systemic hurdles to providing patients with the care they need — a phenomenon called moral injury — can also have a major impact on burnout. Factors like social determinants of health as well as insurance and a hospital’s bottom line tend to hold providers back from providing the best care they can. While this can be frustrating for providers, coming up with workarounds can not only help patients, but also practitioners struggling with burnout

Dr. Jain noted, however, that staffers must be willing to do their part to make changes.

“When asked to participate in committees or the design of activities, people will raise their hands and say, ‘Who’s going to pay me for that time?'” Dr. Jain said.

But those who are reluctant to spare a couple of hours engaging or participating in community efforts are less likely to achieve the positive change that they want.

The Bottom Line

Tackling social determinants of health takes more than sending a shuttle to pick up a patient. To truly achieve health equity, all aspects of society need to contribute toward public health interventions, from providers to cultural orgainzations to professional societies and the government. While doctors may feel limited by what they can do, empathy for their marginalized patients and advocating on their behalf can go a long way.